Chemical Education Journal (CEJ), Vol. 4, No. 1 /Registration

No. 4-8/Received February 8, 2000.

URL = http://www.juen.ac.jp/scien/cssj/cejrnlE.html

E-Mail: toiar@usfca.edu, macdonaldt@usfca.edu

Abstract: Most

of us who have studied in the traditional university lecture/laboratory

based system can recall particular professors whose teaching methods

and whose personalities not only gave the subject a certain character

but also inspired interest in learning. For some, these considerations

were also significant factors in the decision to make chemistry

a career pursuit. In addition, the peer interactions that occur

naturally in lecture, seminar and tutorial meetings, and especially

in laboratory classes are, for many, also a crucial part of the

learning process. And in the reverse sense these interactions,

especially for small classes, allow faculty to have a better perspective

on a student's overall academic abilities. A fundamental question,

therefore, is how to incorporate these elements into a distance

learning course such that degree programs which include these

types of courses are judged equivalent to their traditionally-delivered

counterparts.

One option in designing a distance learning course is to see a portion of it as being internet-driven, as opposed to the Internet providing the sole approach. Thus, it is logical to use the Internet for things that it can currently do well without venturing into technology that is not yet reliable, since multiple failures in a class room setting are frustrating to students and instructors alike. Thus, assuming that the course material is provided "on-line" and in a sophisticated way, some of the interactive aspects from a regular classroom setting may be provided by chat rooms and bulletin boards. However, in addition to the Internet, other possibilities should also be considered. For example, if geographical considerations allow for it, bringing the class together at the beginning and perhaps towards the end of the course could allow for initial interactions, and for group projects to be established with a view to later live presentations to the class as a whole after completion. In addition, tutored-video presentations offer further possibilities. With regard to laboratory work, some experiments might successfully be simulated via the Internet, but this will not allow for the acquisition of actual laboratory skills. Thus, the feasibility of satellite laboratories with supporting instructors should also be considered. As our first step toward distance education this paper focuses on initial efforts at providing Internet support for traditionally taught courses and on student reaction to this.

As a first venture into distance learning, the Department of Environmental Science at the University of San Francisco is exploring the use of the Internet to provide support for various courses in its Master of Science in Environmental Management (MSEM) [1] program, including a course in environmental chemistry. The MSEM program offers specific opportunities as well as challenges since it is a postgraduate program designed primarily, although not exclusively, for working professionals with relevant experience who undertake it on a part-time basis. Moreover, whereas some of the students are recent graduates, some have not been in a school for a decade or more.

In approaching this exercise, a fundamental decision had to be made as to how to use the Internet. Should courses be entirely Internet-driven or should they be Internet-assisted? This was a particularly important decision since the ultimate goal is for the complete degree program to be presented in this way. Moreover the distinction between these approaches defines, at least in some ways, the ability to accommodate different instructional styles. These issues, along with promoting student interest and acceptance of the approach, were considerations of paramount importance.

To further put the above comments in context, it needs to be appreciated that the MSEM program is multidisciplinary, and students enter it with a very broad range of experience and an equally broad range of scientific training and expertise that often overlaps to only a limited degree [1]. Moreover, concepts are not equally familiar or understood with the same facility by everyone in the class. It is not possible, therefore, to assume a common starting point in any given course. These factors make for specific challenges for the instructor and, as will be discussed later, this is one area where the Internet offers motivated students increased opportunities for self-study. Specifically the Internet can enhance learning both pre- and post-course requirements. Students can be provided with the necessary background information for the core course material that will be covered in a class, or with material that extends and enhances knowledge beyond that prescribed in the syllabus, in an integrated and concerted way. In either situation this is achieved without taking up valuable class time, but it is critically important in the former since better prepared students rapidly lose interest if excessive time is devoted to "revision".

It was decided in the initial instance to develop courses that would be Internet-assisted. That is to say, the majority of the material formally prescribed for the course would be presented in the more traditional way, specifically by face-to-face instruction; the Internet would be used primarily in a supporting role. This would provide initial experience for instructors in distance education methodology and techniques and also allow student reaction to be gauged without the risk of large-scale dissatisfaction that could not be corrected for.

The extent of the support developed is substantial, as described below. It should be noted that this support can equally well be used to support "in-house" (traditional face-to-face) instruction, or to teleconferenced classes.

For a program that is intrinsically multidisciplinary, the Internet potentially allows elucidation of the core material in specific courses to be adapted to a variety of different contexts. For example, environmental chemistry, which is a broad subject area in its own right, can be divided into many subtopics that assume different levels of importance for different members of the audience. Subtopics may include the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, the biosphere, and the geosphere. In turn, each of these is equally broad and may be further subdivided. For example, issues within atmospheric chemistry may include global warming, stratospheric ozone depletion, photochemical smog, and acid rain [2]. A similar range of areas can be delineated for each of the other subtopics. Since it is not feasible to cover all of these topics in any given standard-length course in depth, the question arises as to how to address individual academic needs and desires of the students. And this is where use of the Internet comes into its own. Thus support material can be provided on the Internet without intruding into class time. With ozone depletion, for example, required background material, such as basic radical reactions, the concept of a chain reaction, aspects of bond strength, radical stability, reaction rates etc.[3, 4], can be provided by the instructor in a concise and focused way for self-study prior to starting the module in class. At the other end of the spectrum, additional material extending topics beyond that formally required can be similarly provided. With regard to ozone issues, for example, some of the socioeconomic and political issues with regard to the Montreal Protocol [5] could be addressed.

It is also implicit in this discussion that with time this Internet-support approach allows a cadre of subtopics to be accumulated providing the possibility for course material to be rotated as the needs of a particular group of students dictate.

In many ways successful environmental management and a move to sustainable practices requires a holistic view of the environment. In this context, while the Environmental Management program consists of a series of courses, it is important to show their relationship to each other and to integrate them as much as possible. We feel that this is an area where the Internet offers distinct possibilities to achieve this in an interactive and exciting way. With appropriate planning, the Internet allows amalgamation of concepts from a variety of different courses to solve a common problem. In this context, the Internet can be considered as providing a common meeting ground for assembling these perspectives. This notion also carries over into the more practical issue that most environmental problems are broad-based and require extensive collaboration of a team of experts.

As a resource tool, the Internet is becoming progressively more powerful. It offers increasing access to a wide range of databases and other material for both students and instructors alike. While on the one hand this makes for facile collection of information, such material falls into several categories, ranging from on-line government regulatory statutes to research articles to personal opinion pieces. The last category is in stark contrast to peer-reviewed articles in research journals and instructors must be very clear as to what are acceptable sources of reference material. Referencing of material taken from the Internet is still a gray area requiring further debate.

As noted earlier, the MSEM program is designed primarily for working professionals who undertake the program on a part-time basis. They are generally highly motivated and are "self starters". This motivation is a major advantage when using cutting edge educational technology since students are generally interested in using all of the resources available to them to maximize their learning and educational experience and are more likely to engage it fully. There are further and especially important added advantages in working with this group since they have high expectations and are more likely to provide critical and informative feedback to the instructor based on their own professional experience as to the effectiveness of course presentation and the various Internet components.

As alluded to earlier, we anticipate developing the Internet component of our courses in the MSEM program in a series of phases. The first phase is to supplement the face-to-face mode of instruction with Internet materials, to learn from the student reactions, and to improve the material based upon these reactions as we move to more intensive use of Internet technology. A second phase will be to couple the support to teleconferenced classes, and a third phase will be to have some courses as fully fledged distance classes. This last point notwithstanding, from the standpoint of educational philosophy, it was decided at the outset that no course would be taught solely through the Internet. Rather, each would incorporate at least some face-to-face instruction but the relative fraction of the material presented by these different modes would be variable, ultimately depending on the audience and reach of the specific program.

There are multiple reasons underpinning this decision. First, experience within the USF MSEM program, which has been in place now for over 20 years, has shown that many of the students contribute substantially to the program from their own workplace experience. It is important not too lose this extension of classroom experience. It is equally important not to lose the strong networking connections that the students develop with each other. This latter interaction not only serves them well in the study situation, but also in career development. Second, many environmental problems are approached through teamwork between professionals with different types of expertise. Thus, class cohesiveness is important so that students are comfortable interacting with each other. Third, students/instructor rapport is also important since a comfortable classroom setting is generally more conducive to learning. Once the initial introductions are established during a period of face-to-face instruction, we feel that they could be maintained and fostered when Internet instruction is used although some degree of inventiveness may be required on the part of the Instructor.

At the present time we are at Phase 1 of our plan, and as a first step, we have begun providing a major level of Internet support for courses taught in a traditional face-to-face mode. It must be emphasized that the support is pro-active and not passive (i.e., the Internet support is not simply an "on-line textbook") allowing a new dimension to be added to the traditional delivery mode. Internet materials have included six main parts: course notes, worked example problems, quizzes, "extras", bulletin boards, and chat rooms. Similar delivery techniques have been used by distance learning programs at other institutions including Johns Hopkins University in the United States and Waterloo University in Canada [6, 7]. Each of these parts is described below.

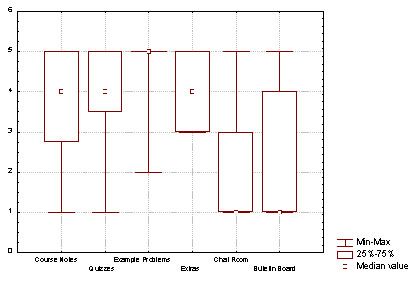

Figure 1 illustrates the student-perceived usefulness of these six materials using a box and whisker plot. The ratings of the various materials ranged from 5 for "very useful" to 1 for "not useful". The student responses spanned the entire range for all but the example problems and the "extras". For those two materials, no student responded that they were not useful. It is very apparent that the material they found most useful was the example problems. The quizzes received the next highest reviews followed by the course notes and extras. The bulletin board and chat rooms did not receive favorable reviews.

Figure 1. Box and Whisker Plot from a student response survey of usefulness of various components of the Internet material.

The class notes comprised a detailed outline of the material covered in the face-to-face classroom meetings. The students found that these materials were most useful for times when they had to miss a class meeting. For a program such as ours, with working professionals, it is more likely that a student needs to miss a class due to work travel or other unforeseen deadlines. Having the material online allowed students who were away on business to access the material from anywhere in the world with an Internet connection. It should be emphasized that at no time was there any indication that students simply opted not to come to class because support material was available online.

The example problems were clearly perceived by the students as the most useful item that was provided on the Internet. This form of Internet assisted instruction was also valuable to the instructor since detailed problems could be solved and available to the student without having to spend valuable face-to-face class time on them. The problems could be ranked by difficulty based on student background, so that a student who is weaker in mathematical skills could focus on certain examples compared to another student who might need a review of certain chemical principles. In addition, the format of the Internet allowed the solutions to the problems to be presented to students in a more useful manner than just as photocopies. Specifically, the Internet allows a step-by-step solution method to guide students through the solution process. In this way, if a student becomes mired at some point while working through the problem by themselves they can get help for the relevant part of the solution to get back on track. In this sense the Internet-material can be regarded as an on-line interactive tutorial. An added bonus to this approach that is not possible with photocopies is that animations and illustrations of time-dependent changes can also be incorporated and demonstrated.

Self-grading quizzes were provided to allow the students to test their knowledge. While the results did not count toward the course grade, they gave students an indication of areas of the course that needed further attention. Students generally found these quizzes to be useful learning tools.

The "extras" that were included on the class web were of three types: background material to help review topics they might not have seen recently, basic reference tables, and additional material extending the scope of the class beyond that specifically required. This serves to help expand the student's learning experience, and also to accommodate differences in student's interests depending on their professional training and background.

The review topics were reported by a portion of the class to be useful. This is as expected since students start the course with different backgrounds and levels of experience. Reference tables were reported to be generally useful, in large part because they provided a measure of convenience and students did not need to look through texts and books at the library. The additional expansion material provided was only used by some of the students. Regardless of this point it seemed that these extra materials worked well for those who did use them. They provided students with convenient reference material so they could spend their time more wisely on learning the course material, they allowed students to brush up on skills, and they allowed interested students to go beyond the scope of what is covered in class to expand their knowledge base, perhaps in relation to a specific need in their work situation.

The chat rooms and bulletin boards saw much less use. Some students used them, but for the most part, they were unnecessary. It is anticipated that these devices would be used more frequently in instructional formats with fewer face-to-face meetings, and that their use would be facilitated since students would have already met each other in the initial face-to-face classes. However, it should be noted that students did report the chat rooms to be useful for group projects. Group projects required students to interact with each other but generally students in the MSEM class live across a large geographic area. The chat rooms allowed them to discuss projects amongst themselves at a time they agreed upon without having to travel through a difficult commute. Students stated that group projects would be much more difficult to implement without the chat rooms.

A final area where Internet assisted learning excelled was through the use of group projects. A large, real-world problem was presented to the students to be solved together in groups over an extended period of time. A simulated water quality problem was developed by the instructor on the computer. The students had to examine this problem and propose solutions for it. The students could gather information using the computer and this information would be available to all the students in that particular group. The groups could easily interact with each other through chat rooms and email as they struggled to solve the problem. The students found this exercise to be incredibly beneficial as a useful application of theory to the "real world".

We kept a record of the number of times each student visited the class web site (expressed as "hits per student") to see whether there was any correlation between their use of the web site and their final grade. Figure 2 is plot of final grade versus number of hits. While there is no obvious correlation, it would be misleading to say that these data demonstrate that Internet assisted learning was not useful. There are many other variables that are not taken into account in this simplistic analysis, such as student background, student expertise, student experience, student ability, and student motivation. Students with strong backgrounds and ability may not have felt as great a need for Internet assistance.

Figure 2. Final student grade versus number of hits on the class web site.

The same group of students who completed the Internet-assisted course referred to above immediately transitioned into a related course with similar-type material. This second course offered no Internet support; it was taught solely in the traditional face-to-face classroom style. After completing this second course, students were asked whether they believed having Internet assistance similar to the first course would be useful and helpful to their learning experience. The students unanimously and forcefully responded that Internet assistance would have been helpful. They were therefore asked to state the type of Internet material that would have been most useful to them. Figure 3 shows the student preferences for Internet materials for the class. The students most wanted example problems and quizzes. There was some demand for course notes, extra material, and chat rooms but no student asked for bulletin boards.

Figure 3. Percent of students wanting the various web site

materials.

In general, the students found Internet assisted learning to be a positive experience. It helped provide appropriate material to a diverse student background to enable a common starting point for instruction. It also extended the learning experience beyond what could be covered during face-to-face class meetings. It must be remembered that the results discussed above are indicative of the student response only to a particular type of course--in this case one that is problem solving oriented. Courses with other emphases may find a greater use from other types of Internet based material. In addition, these were classes that met regularly with the professor and had the core material presented by the traditional face-to face method of instruction. In cases with less face-to-face interaction, we believe there would be a greater demand and use for bulletin boards and chat rooms to promote class interaction and contact with the professor.

Top

Top

Header

Header